Math in q: The limit does not exist

Written on February 11th, 2023 by James

Going beyond the native 64bit math in q/kdb+

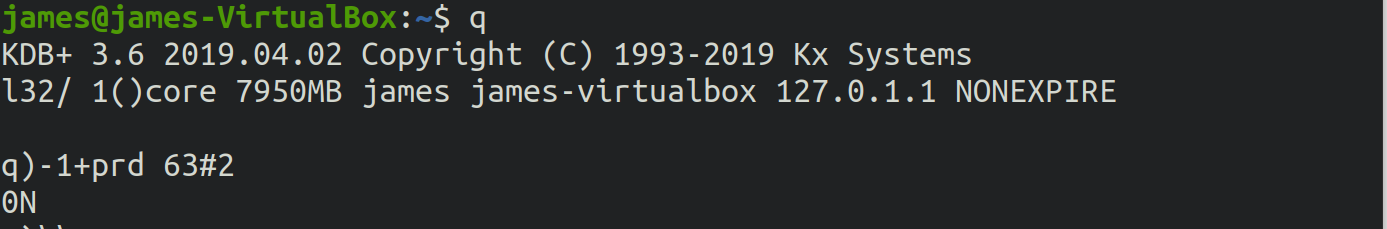

If we are the same type of weird you have probably thought to yourself: “What is the maximum object size that can be encrypted with the sha-256 hashing algorithm?” and quickly ran to google for the answer. If you’re not that weird, then I’ll save you the trip to google and just tell you. It’s 263-1 bytes. Sure, 263-1, but what does that number even look like? Let’s check it out in q/kdb+:

Yikes.

Yikes.

Native math functions in q/kdb+ are limited by the maximum size of the number datatypes involved. The largest datatype in q/kdb+ is a “long” which is takes 8 bytes of data. In different languages this datatype might be refered to as “bigint”, “int64” or “long long”, each represents an 8 byte numerical datatype. Therefore the limit on native numerical calculations q/kdb+ is only 8 bytes of data - that feels a bit tight. Given that numbers in q/kdb+ are signed (positive/negative), that means the largest number you can accurately calculate is 9,223,372,036,854,775,806. The top two numbers (…807 and …808) are reserved for 0W and 0N respectively.

Pathetic.

To top it off, Python3 natively promotes “int” types to “long” types which can have unlimited length and can perform almost any operation (excluding any operation that would convert the “long” to a “float”). To admit that a bunch of snake-charmers could outperform our far superior language? shudders I will not stand idly by while python runs laps around us. If you’re thinking, “This seems like a lot of work, why not just do it in python?”, here is the door.

Now that it’s just us serious programmers, let’s talk about what we need to do to bypass this limit.

Our First Attempt: Partial Products

First, we need a way to represent numbers larger than ~9 quintillion. While there may be several solutions to representing large numbers in an abstract way, I think the most straightforward and human-readable would be to represent each digit as a single number in a vector of longs. In this way, the maximum numerical value of a long would be represented “9 2 2 3 3 7 2 0 3 6 8 5 4 7 7 5 8 0 6”. Great, now in code:

// accepts a number,string or list of numbers

// converts to list of longs

vec:{"J"$/:string x}

So we now have our numbers, or more correctly, our lists of numbers. How do we multiply these numbers together? One of the most common methods of multiplication is called partial products. This method multiplies each digit in one number by each other digit in the second number and aggregating the result. Still confused? Here, watch this video:

One important thing to note here, is that in partial products we don’t consider each digit individually, but rather consider each digit*10n where n is the index of the digit counted from right to left. Because of this we are able to take advantage of the vecorization of one number, but the other must be multiplied by 10n. If I am making absolutely no sense, let’s look at an example:

// our two numbers 3 * 121 = 363

x:3; y:1 2 1;

// multiply each digit by each of the other digits

x*/:100 10 1*'y

300 // (3*100)

60 // (3*20)

3 // (3*1)

// sum

sum x*/:100 10 1*'y

363

// generic partial products code

reverse sum vec[x]*/:{x*prd each #\:[;10]reverse til count x}vec y;

If you are thinking, “that was a softball question”, that’s because it was. In truth, I didnt want to dive too fast into harder problems because I need to explain the concept of digit promotion. If you watched the embedded video above, the digit promotion in that video occurs at about 2:10. When the numbers in a column add up to 10 or more, the tens digit gets promoted to the next column.

Knowing the digits in x will always appear in order, we do not have to worry about multiplying each digit by 10n. However, to assign the appropriate weight to each digit in y we need to multiply by 10n. While this may resolve one side of the equation, our y variable is still subject to the same limitation as always. Let’s look at an example of that:

// our two numbers 3 * 123,123,123,123,123,123,123

x:3;

y:1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3

// correctly weighting our y variable

100000000000000000000 * 1 / too big for q

10000000000000000000 * 2 / too big for q

1000000000000000000 * 3

100000000000000000 * 1

10000000000000000 * 2

1000000000000000 * 3

100000000000000 * 1

10000000000000 * 2

1000000000000 * 3

100000000000 * 1

10000000000 * 2

1000000000 * 3

100000000 * 1

10000000 * 2

1000000 * 3

100000 * 1

10000 * 2

1000 * 3

100 * 1

10 * 2

1 * 3

We cannot weight our y variable properly, because the largest digits exceed the size limit for longs in kdb+/q. However, by switching the x and y digits here, we are able to properly calculate the result. This is because we do not have to weight the x variable.

x:1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3

y:3

// correctly weighting our y variable

1*'y / 1 * 3

// multiply each digit by each of the other digits

x*/:1*'y / 3 6 9 3 6 9 3 6 9 3 6 9 3 6 9 3 6 9 3 6 9

To explain a different way, we are breaking up the y variable into parts based on the digit location.

// 5 * 121,121

x:5

y:1 2 1 1 2 1

5 * (100000 + 20000 + 1000 + 100 + 20 + 1)

-> 500000 + 100000 + 5000 + 500 + 100 + 5

-> 605605

The previous example also gives some insight into how we will tackle the problem of rounding. In two of the numbers in the partial sum, we had to perform digit promotion (“carry the one”). Lets take a look at that example again, but in a more q/kdb+ style to see that promotion a bit more clearly.

// 5 * 121,121

x:5

y:1 2 1 1 2 1

5 * 1 0 0 0 0 0

5 * 2 0 0 0 0

5 * 1 0 0 0

5 * 1 0 0

5 * 2 0

5 * 1

// resolves to

5 0 0 0 0 0

10 0 0 0 0

5 0 0 0

5 0 0

10 0

5

// taking the sum

5 10 5 5 10 5

// taking the div[;10]

// these are the values to be promoted

p:0 1 0 0 1 0

// multiply p by 10 and subtract

5 10 5 5 10 5

- 0 10 0 0 10 0 / (10 * 0 1 0 0 1 0)

-> 5 0 5 5 0 5

// shifting p to the left and add to previous

0 1 0 0 1 0 0 / adding a zero to the right

+ 5 0 5 5 0 5

-> 0 6 0 5 6 0 5

// cut off leading 0

6 0 5 6 0 5

If there are any digits in the resulting sum that are greater than or equal to 10, then we will repeat this process until each digit is less than 10.

Putting this together with the partial products code that we created above, let’s see what we have so far:

vec:{"J"$/:string x}

mult:{[x;y]

m:reverse sum vec[x]*/:{x*prd each #\:[;10]reverse til count x}vec y; / partial products

while[any 9<m;m:(0^next p)+m-10*p:div[;10]m:0f,m]; / digit promotion

(?[;1b]"b"$m)_m / cut off leading 0

}

Finally, we have created a method to multiply one large number (size dependent on memory/list limit) and one 8 byte number. This would solve 99.999% of practical math problems, heck we can even get the answer to 264 right now (using the over iterator and 64#2). Unfortunately, this doesn’t even come close to what python is capabale of; unfortunately for python, this doesn’t even come close to the craziest solution I can think of.

Lets take a different approach.

A Reimagined Attempt: Matrices

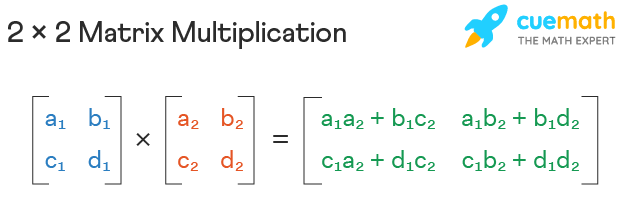

If you are having nightmarish flashbacks to highschool/college, I am sorry, but we must persist. For a quick refresher on matrix multiplication, khan academy has a pretty good video on it here

The main concept of matrix multiplication is described in the image below:  The resulting digit in the first row and first column is the dot product of the first row of the first matrix and the first column of the second matrix. Similarly, the resulting digit in the first row and second column is the dot product of the first row of the first matrix and the second column of the second matrix. This is continued for each row/column until the resulting matrix is formed.

The resulting digit in the first row and first column is the dot product of the first row of the first matrix and the first column of the second matrix. Similarly, the resulting digit in the first row and second column is the dot product of the first row of the first matrix and the second column of the second matrix. This is continued for each row/column until the resulting matrix is formed.

One cool special case in matrix multiplication is the identity matrix. It is a square matrix that when multiplied by a second matrix, will return the second matrix. Lets see an example:

(1 2 3) x (1 0 0) = (1 2 3)

(4 5 6) (0 1 0) (4 5 6)

(0 0 1)

// Breakdown

1*1+2*0+3*0 1*0+2*1+3*0 1*0+2*0+3*1 -> 1 2 3

4*1+5*0+6*0 4*0+5*1+6*0 4*0+5*0+6*1 -> 4 5 6

By multiplying the identity matrix by a scalar, we can achieve the same results as multiplying the original matrix by a scalar

(1 2 3) x (1 0 0) x 2

(4 5 6) (0 1 0)

(0 0 1)

OR

(1 2 3) x (2 0 0) = (2 4 6)

(4 5 6) (0 2 0) (8 10 12)

(0 0 2)

// Breakdown

1*2+2*0+3*0 1*0+2*2+3*0 1*0+2*0+3*2 -> 2 4 6

4*2+5*0+6*0 4*0+5*2+6*0 4*0+5*0+6*2 -> 8 10 12

But this scalar would still be subject to the same 8 byte limitation as any number in kdb+. Unless…

(1 2 3) x (1 0 0) x 315

(4 5 6) (0 1 0)

(0 0 1)

OR

(1 2 3) x (3 1 5 0 0) = ( 3 7 16 13 15)

(4 5 6) (0 3 1 5 0) (12 19 43 31 30)

(0 0 3 1 5)

Wow, lets take a closer look at that example. This time we will focus on the top row of our first matrix.

(1 2 3) x (1 0 0) x 315

(0 1 0)

(0 0 1)

OR

(1 2 3) x (3 1 5 0 0) = ( 3 7 16 13 15)

(0 3 1 5 0)

(0 0 3 1 5)

// Using our previously discussed rounding method

( 3 7 16 13 15) -> 3 8 7 4 5

// Why is this significant?

123 * 315 = 38745

Incredible. By replacing the 1s in our identity matrix with the vectorized representation of our scalar number, we are able to achieve a vectorized representation of the result. What’s better is that at no point are we multiplying numbers greater than 10. With this method we have completely eliminated any 8 byte number limitations, our only limitation now is the size of the multiplication matrix. That limit is a bit more difficult, but it is at least restrained by the internal kdb+/q list limit of 264-1 in q3.* or 2 billion in q2.*

Before we get too carried away with the math of it all, lets get all this to work in code.

// mmu function requires floats instead of longs

vec:{"F"$/:string x}

mult2:{[x;y]

m:vec[y] mmu c (rotate[-1]@)\vec[x],(c:-1+count vec y)#0f; / matrix multiplication

while[any 9<m;m:(0^next p)+m-10*p:div[;10]m:0f,m]; / digit promotion

(?[;1b]"b"$m)_m / cut off leading zero

}

If you are reading this code and thinking: “Hey James, wouldn’t sum vec[y] * ... do the same thing as vec[y] mmu ...?”

Then I am quite impressed. Yes it will, but for reasons that are well above my understanding, mmu is faster and consumes less memory in just about every case.

If you are reading this code and thinking: “Oh yes, I understand why vec[y] mmu ... is faster than sum vec[y] * ... in this situation.”

Then please share your wisdom with me. @Arthur_Whitney my DM’s are wide open.

If you are reading this code and thinking: “I don’t understand anything that I am looking at…“

Now you’re starting to sound like a proper kdb engineer.

Our code is looking quite good already, but we are not quite optimized yet. There is still more to be gained in the digit representation.

Maximizing Each Digit

Every digit in our vectorized representation of these numbers contains 8 bytes, if each digit is 9 or less, we are hardly even using 1 byte of data per digit. By increasing our digit base from 101 to 109 we are able to retain human readability and optimize our operator. With this new base, our maximum digit will be 999999999 instead of 9. We keep this well below the maximum size of a long to allow native math operations on each digit, otherwise our mmu would break down.

The hardest part of this is converting our vec function. This is because we can no longer treat each character in the string as a digit, we need to concatenate strings at specified intervals. Initially, you might think to group the first 9 characters together, then the next 9 and so forth. However, when the number of characters is not a factor of 9, this method will incorrectly leave less than 9 characters in the final digit. Let’s see an example using 2 characters at a time instead of 9:

// 12345 * 51 = 629595 (correct result)

x:12345

y:51

vec:{"F"$/:(0N,x)#string y}[2]

// vec[x] -> 12 3f

// vec[y] -> 51f

// matrix multiplication

m:vec[y] mmu c (rotate[-1]@)\vec[x],(c:-1+count vec y)#0f;

// 51f * 12 34 5f -> 612 1734 255f

// digit promotion

while[any 9<m;m:(0^next p)+m-10*p:div[;10]m:0f,m];

// 0 7 8 7 9 5f (incorrect result)

It might be possible to adjust our digit promotion function to accomodate this format, but I think the much easier solution would be to adjust how we group our number characters. In cases where the number of characters is not a factor of 9 (or whatever number we specify), then we will add zero characters to the front of the string until it is.

rt:{(0N,x)##[(x*ceiling count[y]%x)-count y;"0"],y} / reverse "take"

vx:{"F"$/:rt[x] raze string y} / vectorize in x sized groups

vx[5] 1234567890123 / 123 45678 90123f

vx[9] x:90123456789123456 / 90123456 789123456f

vx[9] y:"123456789123456789" / 123456789 123456789f

// matrix multiplication

m:vx[9;y] mmu c (rotate[-1]@)\vx[9;x],(c:-1+count vx[9;y])#0f;

// 11126352491342784 108549000493685568 97422648002342784f

// digit promotion

while[any m>sum(9-1)(10*)\9;m:(0^next p)+m-prd[9#10]*p:div[;prd 9#10]m:0f,m]

// 11126352 599891784 591108216 2342784f

Its critical to note that the last item in the result has only 7 digits. This number should really be 002342784, but q/kdb+ isn’t in the habit of storing leading zeros. The simplest way I can think to deal with this is by converting back into a string and adding zeros to the front of each item where the item has less than 9 digits. While we are at it, lets add a written format function that will add commas to make it easier on the eyes.

fmtx:{[n;x]raze string[x 0],(neg[n]##[n;"0"],)'[string 1_x]} / adds 9 zeros to each item then takes last 9 digits

m:11126352 599891784 591108216 2342784f

fmtx[9] m

// "11126352599891784591108216002342784"

// written format func

wfmt:{({x,",",y}/) @[;0;string "F"$]rt[3] raze string x}

wfmt fmtx[9] m

// "11,126,352,599,891,784,591,108,216,002,342,784"

Great, now we have a multiplication operator that accepts numbers in a list, string or long format and will return the result in a string format to be used again in another multiplication operation if we so choose. Additionally if the number gets too long, we have our wfmt funciton that can break it up into a familiar readable format for us.

And that’s all there is!

Isn’t it beautiful?

rt:{(0N,x)##[(x*ceiling count[y]%x)-count y;"0"],y} / reverse take

vx:{"F"$/:rt[x] raze string y} / vectorize in x sized groups

multx:{[n;x;y]

m:vx[n;y] mmu c (rotate[-1]@)\vx[n;x],(c:-1+count vx[n;y])#0f;

while[any m>sum(n-1)(10*)\9;m:(0^next p)+m-prd[n#10]*p:div[;prd n#10]m:0f,m];

(?[;1b]"b"$m)_m

}

fmtx:{[n;x]raze string[x 0],(neg[n]##[n;"0"],)'[string 1_x]}

// example use

wfmt fmtx[9] multx[9] . (x; y)

A Special Bonus: For Python Devs

If you aren’t familiar with the q/kdb+ language and have made it this far, congratulations. This isn’t an easy lanuguage to understand at first and it’s not fun to read either. Writing and understanding a complex string of numbers and special characters can feel like a super power to many qbies, hence why we call those with that super power ‘q gods’. And with great power, comes great responsibility. Mainly, to write clear, understandable code that it is easily maintainable. I say to hell with that responsibility, let’s write something ungodly. Something so dense and so confusing that python devs have no choice but to stop reading.

Let’s rewrite everything without using a single word in the code: 😈

// NO WORDS ALLOWED !!

kr:"k" "{,/|(0;(#y)-1)_y}" / simplified k conversion of rotate

krt:"k" "{(0N,x)##[(x*-_-(#y)%x)-#y;\"0\"],y}" / direct k conversion of rt

kvx:"k" "{\"F\"$/:krt[x;,/$:y]}" / direct k conversion of vx

kfmt:"k" "{,/($:y 0),((-x)##[x;\"0\"],)'$:1_y}" / direct k conversion of fmtx

kwfmt:"k" "{ {x,\",\",y}/@[;0;$:\"F\"$]rt[3;,/$:x]}" / direct k conversion of wfmt

multk:{ {(?[;1b]"b"$x)_x}{(|/)y>(+/)(x-1)(10*)\9}{(1_p,0f)+y-(*/x#10)*p:(_:)%[;(*/x#10)]y:0f,y}/kvx[x;z] mmu c kr\kvx[x;y],(c:-1+(#:)kvx[x]z)#0f}

Is it cheating if 90% of it is written in k? Absolutely not. I make the rules.

Conclusion

We went over a lot in this post, partial products, matrix multiplication and lots of q code. In the end, we were able to write a function that is capable of accurately multiplying 2 numbers well beyond the 64 bit limit in q/kdb+. If you want to see all the code we went over today, you can check it out in my github gists here.

Although the infinite math available in python was not my inspiration for this post, we did loosely follow the same steps as the developers for python (convert number to list, maximize the size of each list item, etc.). However, python uses the Karatsuba algorithm for multiplication instead of our matrix multiplication, and they are able to store up to 32 bytes in each list item. If you want to read more about how python supports unlimited data in their number types, you can read this article. Who knows, maybe I will come back later and take another crack at unlocking infinite math in kdb.

Thanks for reading, I know math isn’t everyone’s favorite subject and this post is littered with it. If you have any questions, comments, or you think you can write a better multiplication operator, definitely reach out to me using one of my linked accounts or leave a comment (if I ever get those things set up).

As for the limit of our new multiply function? Well, you probably will run out of memory before you hit it, but it can hold 9*(264-1) digits. Now if only we had a way to calculate that number…

Feel free to share